Holy Night, Holy Supper

Crashing out about Christmas, late in time

Kutya

6 cups water

2 cups wheat kernels

2 Tbsp liquid honey

1/2 cup poppy seeds

Boil wheat in water for 3 to 4 hours until soft. Add honey and cook for about 30 minutes more. The wheat is ready when the kernels open and the fluid is thick and creamy. Add the poppy seeds. Cool to room temperature, then refrigerate in a jar. Substitute apple pieces, walnuts, or pecans instead of poppy seeds. Keeps for about one month. Serves 8.

Three-Ginger Gingerbread Cookies

4 1/2 cups all purpose flour

2 tsp baking soda

2 tsp ground ginger (or more)

1 1/2 tsp cinnamon (or more)

1/2 tsp cloves

1 tsp salt

1 1/4 room temperature butter (or margarine)

1 1/2 cup packed brown sugar

1/2 cup fancy molasses

2 large eggs

2 Tbsp grated fresh ginger

2/3 cup finely chopped crystallized ginger

Cream butter and sugar together; add molasses, egg, and grated fresh ginger. Combine dry ingredients in a bowl and gradually add to the molasses mixture in several installments. Mix well.

Add crystallized ginger. Mix. Divide dough in half, flatten into a disk about one inch thick, and chill for several hours. Roll out and cut into shapes. Bake at 350 degrees F for 12 to 14 minutes. Decorate.

Sviat Vechir

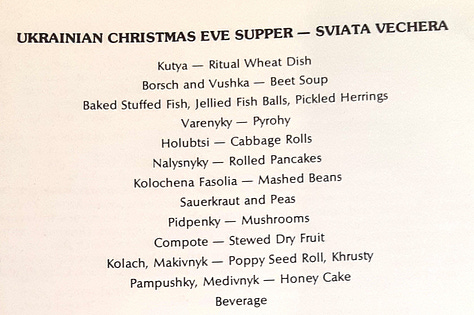

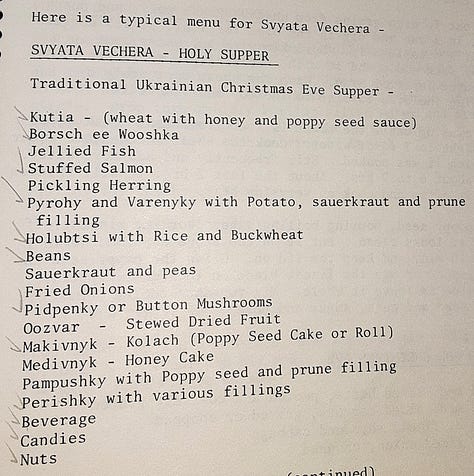

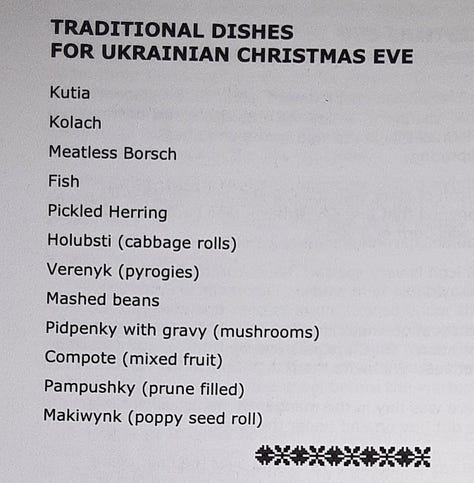

Above is one possible non-Cyrillic spelling of an event known in English as Holy Supper, a feast of twelve dishes traditionally prepared (at least in Canada) by Ukrainian Catholics and Orthodox Christians on Christmas Eve.1 The meal is somewhat similar to the Italian American feast of the seven fishes. It’s a lot of courses, ostensibly excluding meat and dairy, which vary according to the food voice of the particular cook or family, and which blur the line between feasting and fasting.

Holy Supper begins with kutya, a kind of stewed wheat porridge made with honey and poppy seeds, and sometimes with fruit and nuts. The recipe above is from Ukrainian Canadian author Marion Mutala, who inherited it from her mother Sophie. It can be found in Baba Sophie’s Ukrainian Cookbook, published in 2022, or in the Ethnic Cookbook compiled in 1981 by the editors of the Saskatoon Commentator.2 Like many symbols, rituals, and traditions, kutya is interpreted slightly differently depending on the person or family. In 1970 the UCWLC of Saint George’s Cathedral in Saskatoon suggested it might have originated as an offering to an unnamed sun god.3 The UWAC of Regina asserted in 1984 that the wheat represents the staff of life and the honey represents the Spirit of Christ.4 The UCWLC of Saint Basil’s in Edmonton stated in 1967 that the wheat, honey, and poppy symbolize the fertility of God’s nature, and together they make a dish that signifies prosperity, peace, and health.5

Other dishes are less rich with meaning, and are thus more flexible. One might have mashed white beans, or broad beans, or split peas. One might make poppy seed roll (makivnyk) or poppy-filled doughnuts (pampushky). One might prepare any number of fish dishes, ranging from pickled herring to jellied pike cakes to rice stuffed salmon.6 Meatless borsch and cabbage rolls are very common, but for my thesis research I spoke with a woman whose mother never made borsch, and holubtsi can be made with rice or buckwheat, sour cabbage or sweet cabbage, tomato sauce or mushroom sauce, etcetera etcetera. There must be twelve dishes to represent the twelve apostles. Unless that’s too much work, for too few hands and too small a crowd. Then one can leave off the dried fruit compote, because nobody likes it anyway.

Marusya Bociurkiw, another Ukrainian Canadian author (of a different genre), claims that “without properly made varennyky, the meal would have no centre.”7 But who determines what is properly made? Ukrainian chef, activist, and cookbook author Olia Hercules claims, like many others, that varenyky ought to be served swimming in butter, but Sviat Vechir is technically supposed to be dairy free. Ultimately, the primary cook (often a woman) decides what rules to break and what traditions to uphold. They can therefore forgo some religious significance in favour of making foods they and their kids actually like. Most kitchens are not micro-managed by canon lawyers.

Feasting & Fasting

The deliberate forbearance from meat (and sometimes dairy) is not fasting, per se, but rather abstinence. At least, that’s what I’ve always been taught. In my experience, Roman slash Latin Catholics in contemporary Canada rarely abstain from meat on Christmas Eve.8 But we do fast sometimes in Lent, and abstain from meat (or make some other kind of penance) on Fridays throughout the year.

Understandings of fasting can differ as much as understandings of kutya, but there are commonalities. Many people see it as a form of disciplining the body so as to discipline the soul, practicing self-control in relatively small matters so as to build up resistance to larger temptations. It is a way of separating oneself slightly from this world to as to focus more on what really matters (i.e. God). We don’t fast because food is bad, or because enjoying food is bad. These things are good. Cheese is proof that God loves us and wants us to be happy. But it is not the ultimate good.

Preparing to celebrate the incarnation by taking concrete steps to refocus one’s attention on God makes sense to me. In the RC churches of my acquaintance, they do this by changing the Mass a bit for the four Sundays of Advent (the candles on the Advent wreath are lit, the vestments are purple, the Gloria is omitted, etc.). This season is marked as different. It’s not Ordinary Time, but it’s also not Christmas yet. By Christmas Eve, the anticipation should have built to a high crescendo; the in-betweenness of Advent is distilled and concentrated. One might spend the day rolling holubtsi and boiling varenyky and looking forward to a (hopefully) more joyful and restful meal the next day, or one might flip flop between doing school-related busywork and half-watching Hallmark Christmas movies while drinking sadly non-alcoholic beverages in long the hours leading up to Midnight Mass. Hypothetically. One cannot yet celebrate, but the celebration is so close that the routines of day-to-day become borderline impossible.

Christmas Eve is not the feast. But let’s be real. Eating twelve dishes is not a fast.

The True Meaning Of…

In a 1908 essay, G. K. Chesterton writes a lot of tetchy, critical things about how Christmas is celebrated in early twentieth century Britain, many of which I, a famously tetchy and critical person, agree with. One theme in particular arises, that people should not celebrate Christmas “slouchingly,” half-heartedly, or ungracefully.

Let us be consistent, therefore, about Christmas, and either keep customs or do not keep them. If you do not like sentiment and symbolism, you do not like Christmas; go away and celebrate something else.9

Sviat Vechir is not a whole-hearted fast or a whole-hearted feast, but it is certainly whole-hearted (not to mention sentimental and symbolic). There is ceremony in the round braided kolach bread inserted with a candle, and the sheaf of wheat named didukh (grandfather). Even if a family does not follow all the traditions outlined on the obligatory Christmas Eve page of any self-respecting Ukrainian Canadian community cookbook, the attempt to make twelve dishes of any kind the night before a feast is so clearly irrational that it must be at least partially motivated by custom.

I’m not very familiar with Orthodox or Ukrainian Catholic Lenten traditions, but I cannot imagine that a twelve course meal is part of them. Sviat Vechir is unique. The Holy Supper reflects the fact that, in the words of Lutheran pastor and podcast host Donovan Riley, “Christmas is illegitimate and weird.”10 Messengers share tidings of great joy and terrify everyone. A baby is born and a bunch of other babies are killed. A meal is prepared that is abundant and delicious, but also penitential in its difficulty, exacerbated by the exclusion of classic Ukrainian Canadian ingredients like butter, curd cheese, and pork. Christmas is weird and it is hard, due to end-of-term burnout and awkward conversations with extended family and unanticipated illnesses or injuries and the fact that the dishwasher or vacuum cleaner or furnace will always stop working while Grandma is visiting. One hopes, I suppose, that it is also joyful.

Boiled in My Own Pudding

I’ve spent the last month feeling as though I ought to write something about Christmas. Not only is it a good time of year for Food Traditions™ (see the gingerbread recipe above), but it is also a season slash festival slash holiday that I have a lot of opinions about. Unnecessarily strong, antagonistic, and particular opinions, which are backed up by Vibes rather than considered arguments. Setting up the Christmas tree before December? Bad Vibes. Decorating the Christmas tree with as many mismatched, homemade, store-bought, inherited, and downright ugly ornaments as possible? Good Vibes. Inflatable lawn ornaments? Bad Vibes. Beating back the darkness with multi-coloured LEDs? Good Vibes. White hot chocolate? Bad Vibes. Terry’s Chocolate Oranges? Good Vibes. You see the vision: there is none. I’m driven almost entirely by what one might charitably call sentiment and symbolism (but more accurately nostalgia and fear of change).

I like to share these opinions with people. I openly malign Roommate B’s Christmas playlist. I have rants about the best and worst and most pretentious, precious, and overcomplicated Christmas cookies. I nearly started a riot when certain persons wanted to set the tree up on November 23rd, because I subscribe to the Chestertonian view that “there is no more dangerous and disgusting habit than that of celebrating Christmas before it comes.” Because nothing helps cultivate hope and re-focus attention on God like being ceaselessly mad about everything.

Writers running the gamut from C. S. Lewis to Ruby Tandoh (whom I’ve cited elsewhere) have noted that the relentless busy rush leading up to Christmas is maybe sometimes not great.11 Lewis is more thoroughly opposed, especially when it comes to all the new products promoted by shopkeepers around Christmas, but that’s just because he never had the chance to experience Terry’s Orange Hot Chocolate Bombs. Tandoh, meanwhile, loves the novelty, the absurdity, and the Malteser reindeer things, and finds herself “buying even the most ghastly crap in the spirit of Christmas indulgence.” But “excitement is exhausting,” especially when it stretches from November to New Years. One must integrate moments of normalcy in order to bear it.

Like Tandoh, by the time the 25th arrives, I’m always tired and strung out. This year was particularly bad. It would be nice if Chesterton’s ideal could actually happen:

It is the very essence of a festival that it breaks upon one brilliantly and abruptly, that at one moment the great day is not and the next the great day is. Up to a certain specific instant you are feeling ordinary and sad; for it is only Wednesday. At the next moment your heart leaps up and your soul and body dance together like lovers; for in one burst and blaze it has become Thursday.12

The Christmas rush does not facilitate this. Neither does spending a month and a half being mad about the Christmas rush (and stressing out about unemployment and starting a new job and imminent roommate changes etcetera etcetera).

The Great Day

I didn’t do Christmas very well this year. I was still worried and mad about all the things I was worried and mad about throughout Advent. I didn’t get a chance to make kutya or three-ginger gingerbread cookies. I was still the same flawed and frustrated person after Midnight Mass as I was before. There were many changes to our usual family traditions, and I felt weird about them. Also, my mom had the flu.

I can imagine that perhaps, occasionally, a woman preparing twelve meatless dishes for an intergenerational family gathering might find afterwards that she is tired. And that the recipes didn’t turn out as well as she had hoped. And that the kids wouldn’t eat the dried fruit compote or the pickled herring. And that there are too many leftovers to manage. So why bother?

We do these things for the sake of sentimentality and symbolism. But joy, the song and dance of soul and body, is not the automatic outcome of a successfully completed series of tasks. I once heard a priest say joy is a choice. The choice to lean into the weird, and laugh at it a bit, not out of dismissal but out of delight and surprise and awe. The choice to look past and look through the hard, to realize that maybe someone is sick this year, but nobody’s in the ER on Christmas Eve, and maybe there was no family cookie baking, but there was roommate cookie decorating. On Christmas Eve we had delicious cold lobster with hot butter (courtesy of my dad), and on Christmas Day we had spectacular duck confit (courtesy of my mom), and on the Feast of Saint John the Evangelist we had Acadian tourtière (courtesy of me). Traditions old, new, and delicious.

And, at the last, Christmas isn’t something you do, anyway. Cooking is something you do, but a feast is about more than just food. A feast is a gift; you receive it.

In the Julian Calendar followed by many Orthodox Christians and some Ukrainian Catholics, Christmas Eve is January 6th, and the twelve days of Christmas last until January 19th. So what I’m saying is this post isn’t really late.

Marion Mutala, Baba Sophie’s Ukrainian Cookbook (Saskatoon: Millennium Marketing, 2022), 18; Sophie Mutala, “Kutia (Cooked Wheat Dessert),” in Ethnic Cookbook: A collection of ethnic recipes from the kitchens of Saskatoon and area (Saskatoon: Saskatoon Commentator, 1981), 128.

Mrs. Nick Blocka, “Our Christmas Traditions,” in Cook Book (Saskatoon: Ukrainian Catholic Women’s League of Canada, 1970), 9-10.

Ukrainian Women’s Association of Canada, “Kutia,” in Ukrainian Daughters’ Cookbook (Regina: Centax Books, 1984), 10.

Ukrainian Catholic Women’s League of Canada, “Ukrainian Christmas Tradition,” in Culinary Treasures: Centennial 1867-1967 (Edmonton: Bulletin Commercial Printers, 1967), 74.

Famously, fish and seafood are not considered meat by the Catholic Church, and are therefore permitted on days of fasting and abstinence. The same is true of beaver.

Marusya Bociurkiw, Comfort Food for Breakups: The Memoir of a Hungry Girl (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2007), 159.

Within the Catholic Church there are six liturgical rites, or traditions, and within these there are 24 particular churches. Ukrainian Greek Catholics are one such particular church, in the Byzantine rite. The majority of Catholics in North America are part of the Latin rite. Since all Catholics recognize the authority of the Roman pontiff, it’s not exactly incorrect to refer to all Catholics as Roman Catholics, but the Ukrainian Catholics I know generally reserve that term for members of the Latin rite. I’ve never heard anyone use the term “Latin Catholic” in conversation. Nicholas LaBanca, “The Other 23 Catholic Churches (Rites) and Why They Exist,” Ascension Press Media, January 21, 2019, https://media.ascensionpress.com/2019/01/21/the-other-23-catholic-churches-and-why-they-exist/

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, “Christmas,” in All Things Considered (1908; reis., Duke Classics, 2012), Libby.

Donovan Riley and Christopher Gillespie, hosts, “Chesterton—Mankind would have a much worse time if there were no such thing as Christmas or Christmas dinners,” December 20, 2025, in Banned Books, produced by 1517 Podcasts. I don’t agree with everything they say on this podcast, but this statement was real.

Clive Staples Lewis, “What CHRISTMAS means to me…,” in God in the Dock—Essays on Theology and Ethics (London: William B. Eerdman’s Publishing Co., 1957); Ruby Tandoh, “Digested: Christmas,” in Eat Up! Food, Appetite and Eating What You Want, read by Ruby Tandoh (Random House Audio, 2022), Libby audio ed., 7 hr., 46 min.

Chesterton, “Christmas.” He’s making a joke here about how those who celebrate Thor’s Day might hypothetically feel each week, but I thought this was funny because the 25th was a Thursday in 2025.

Just to additionally note that the tourtiere was pretty fantastic also.